Moodle has been used for over 10 years, and yet 'What comprises a good Moodle course'? is still a hot topic.

Some top tips from Yong Liu include:

1) Mobile learning is key, and gamification is built in as much as possible (although it can be heavy on the budget), plus integration of social media. It is important to automate as many of the processes as possible, while also personalising the learning. However, using an animation or the latest technology, may remove the focus from the learner.

2) It is important to offer opportunities for students to link exiting knowledge with new knowledge. Multimedia can help people learn by helping them select organise and integrate information and understanding (Mayer, 2016). We can only take in visual and aural input, but not two aural inputs at the same time. We can also only take in a limited amount of information at one time. To help alleviate the stress we need to remove redundant and gratuitous graphics, place text near graphics, and explain graphics with audio instead of text if possible.

3) A good Moodle course should simplify complex content, by, for example, segmenting content into small chunks. Information should be precise and exactly what they need, without additional information. Activities also have collaboration, peer teaching - activities where the students do the work themselves. We foster generative processes (Mayer, 2016) by letting the student 'pull' knowledge and selecting what they want when they need it. Use conversational tone and pedagogical agents.

What tips could you add to this list? What have you found works a treat for your learners in Moodle?

Image: Design. CC ( BY SA ) licensed Flickr image by Miquel Lopez: https://flic.kr/p/5oQgCo

Thursday, December 1, 2016

Wednesday, October 12, 2016

Changing customer experiences through Moodle

At New Zealand Language Centre the students tend to be English language learners, where there are over 25 nationalities represented at the school.

At New Zealand Language Centre the students tend to be English language learners, where there are over 25 nationalities represented at the school.

Pete Jones shares that, he sees his 'customers' in relation as the students, the academic staff, and the administrators. Prior to implementing the Moodle project all the diagnostic, placement tests were completed as paper based and had to be manually marked, within very tight time frames. Now students complete most of their placement test online, and the reading, grammar, and vocabulary tests are now automatically graded.

Moodle was a catalyst for NZCL to review and update their placement test. The existing test had many of the gap fill type questions, where the responses are sometimes not cut and dried. It also encourages students to learn the language in a decontextualised way. The new test has an embedded cloze type test that offered a contextualised scenario, where the organisation could be more confident in the responses that were being given in the test. It has been well worth the investment.

Previously, student would write their contact details onto a form, and then someone had to decipher the handwriting and add the details to a database.

One of the next steps is to develop a theme for Moodle, that would also complement the new web site.

To sum up, the Centre has met their original objective. Over 70% of students said they preferred this system "it is more convenient than the paper test". For those who didn't prefer it the reason given was previous familiarity with paper based tests. Some of the unintended consequences including having to look at the whole orientation of new students, which has meant providing more time to welcome the students - and this has resulted in a longer timeframe for the placement tests removing a lot of stress for the academic staff. In addition, some of the staff have signed up to the Learn Moodle MOOC.

Image: HP Mini. CC ( BY NC ) Flickr image by Tuesday Digital: https://flic.kr/p/6tg3kw

Wednesday, October 5, 2016

Creating meaningful assessments...

What does a meaningful assessment look and feel like? How can Moodle be used to enhance a learner's assessment experience? In this session I covered a few of the key factors to consider when designing assessments, as well as some of the activity types in Moodle that can be used. I dipped into a couple of examples to illustrate what can work well ... and what might not. By the end of the session the idea was that people would have some additional ideas to take away and use when creating assessments in Moodle, along with considerations that would help ensure that the assessments work for your learners and for you.

The lived experience of sing Moodle for online exams

At Nelson Marlborough Institute of Technology (on the South Island of NZ) all of the exams are paper based. In the Bachelor of Nursing (Year 1 course), there are 2 multi choice exams requiring 90% pass rate. They get the questions the week beforehand and work in a study group to debate the responses, and then come in to respond to the same questions.

Printing costs were massive, with exams being 6 or more pages in length, and had to be printed twice. The exams were also all hand graded. So they turned to Moodle.

All of the exam questions were uploaded into a Moodle forum to download or print them off themselves. The students were still able to get into their study groups to debate. In preparation to do the exam on a screen 'spot tests' were administered throughout the semester to familiarise students. There was also discussion around etiquette for once the results were released because the feedback was not released until after they had finished.

Some of the benefits were:

Printing costs were massive, with exams being 6 or more pages in length, and had to be printed twice. The exams were also all hand graded. So they turned to Moodle.

All of the exam questions were uploaded into a Moodle forum to download or print them off themselves. The students were still able to get into their study groups to debate. In preparation to do the exam on a screen 'spot tests' were administered throughout the semester to familiarise students. There was also discussion around etiquette for once the results were released because the feedback was not released until after they had finished.

Some of the benefits were:

- questions were randomised

- cheating was minimised by the format of the exam (questions provided in advance, and randomised questions, so there isn't such an advantage to going through and highlighting the exams)

- automatic marking

- results released immediately

- printing and paper costs reduced

- it was easy!

There were some challenges including:

- PC lab room availability

- increase in number of invigilators

- iPads were not so user friendly (the Moodle page kept freezing, and wouldn't change the page and created a lot of anxiety. Students were persistent and carried on, and everyone passed)

- WiFi connections (60 students were all accessing the same thing at the same time)

In terms of the future, at NMIT there is a focus on moving more exams online, and ideally for all the students to use their own devices and sit the exam in one room.

Moodle at Northtec: Past, present and future

In 2003 the Flexible Learning team created the Bachelor of Nursing, and built on the 'we just did it' champions. In 2008 'Cyclone Vasi' hit, with a passion for students and learning - and a wide range of ideas. Her managerial skills brought a structure and a methodology with eLearning. In 2009 the 1st instructional designer joined Northtec, and helped identify key design principles which were essential for course design. At the time they had three Moodle instances running. One of them is the 'archive site', which provides a copy of existing courses, which means that Northtec don't have to have sophisticated disaster recovery processes and backup.

By 2012, Northtec was trying to provide some rigour and structure into the quality control of courses. On the 'live server' (NorthNet) they have a 'development category' with restrictions (for example, teachers can't enrol students into courses, nor can they change the name, or shift the course into another category. They used a student focus group to get the look and feel right. The students were looking for something a bit more dynamic.

Northtec are about to move to 3.1, and Moodle is still hosted off site. There has been some feedback around the lack of communication around version changes, so they have made a big effort to address this.

For some of the students (in particular Nursing) Northtec have developed a version of Moodle that installs off a USB. They can install the version onto their hard disk, and they can get to all of their course materials while 'off the grid'.

Plans for the future are dependent on the ability to upskill staff. How do you put a good online course together? Standardisation of courses is important, although they only have one instructional designer. There is a planning process to work through before releasing to students. The keys are staying flexible, and adapting as needed.

Tuesday, October 4, 2016

Is your preference thinking, feeling, intuiting or sensing?

- Thinkers tend to collect and consciously analyse data.

- Feelers are open to emotions and their consequences.

- Intuitors don’t find detail useful, and act on on their decisions, although they may not be aware of how they reached the decision.

- Sensors tend to be kinaesthetic and rely on their senses to guide their reactions and actions.

Marchant (2014) identifies that everyone uses all four. However, many of us “favour one way over the other three, sometimes markedly so” (Para. 15), and it’s being cognisant of whether we favour one over another that can be helpful.

Given these factors, I will now focus on the intuitor-type of person In a coaching context; in particular I’ll identify aspects that might help me coach this person, and what I might need to keep an eye open for.

If I am working with a person who strongly identifies as an intuitor type I would expect that they are likely to:

- be focussed on potential and future possibilities (although these can seem unrealistic)

- look for patterns and relationships

- be (apparently) impulsive because they seem to react rather than taking time to consider ‘the facts’

- have a wide range of ideas

- not be keen on detail or data

- enjoy using their imagination

- enjoy being creative and inventive

- like to work with conceptual ideas and information

- be idealistic

- be focussed on bigger picture rather than processes and guidelines

I would try to shape coaching sessions to help ensure that there are plenty of opportunities for my coachee to talk through their ideas (including philosophic underpinnings and principles). During these descriptions I would gently encourage them to unpack a bit more detail, but in a way that signals I am curious about, and value, their insights. Supportive questions might be around encouraging the coachee to consider how other people in their context respond positively to their ideas, and, if appropriate, I would also ask questions about other (online) communities and places the coachee could share, discuss, and develop ideas further.

One of the things I would need to keep an eye on is that the coachee doesn’t end up going through similar cycles and not recognising them as such - especially if they are making the same mistake each time. For example, a coachee might describe a series of situations where they receive the feedback ‘we don’t know what you are working on most of the time - or why’. It could even have led to misunderstandings to the point where they have been pulled in for a meeting and questioned about what they are spending their time doing. Usually, it’s a case that the coachee has been so completely focussed on a task or project that they haven’t taken the time to communicate their progress to anyone else, and have seen the feedback as a minor annoyance - until, to their surprise, serious questions start to be asked about their performance.

In situations like this one, I would encourage my coachee through a deductive process:

- to consider the implications of their complete focus (i.e. the bigger picture),

- and how the positive progress they are making (i.e. the details),

- could be (creatively) communicated with any stakeholders who needed to know so that these stakeholders can / will continue to support and fund the piece of work on which the coachee is focussing,

- and finally, encourage the coachee to identify ways they can share with co-workers, managers, family and friends their “preferred intuitive information gathering preference” (Edward, n.d., Para. 5).

The central thing here is to support my coachee to clearly identify the ‘why’, so that they have a clear reason and motivation to carry through with a necessary action (possibly in a creative way). In this example, it would be a strategy that could also ensure that they keep their role! In turn, by opening up awareness and lines of communication, ideally it would lead to increased support and recognition of the value of the work the coachee is doing.

References

Marchant, J. (2014). Thinker, feeler, knower, sensor? Retrieved from http://www.emotionalintelligenceatwork.com/resources/thinker-feeler-knower-sensor/.

Southern Institute of Technology (a). (n.d.) Transformational Coaching and its outcomes (Module C) [Lecture notes]. Retrieved from CBC106 (NET).

Monday, September 12, 2016

Making the change we know in our hearts is essential…by building a coaching culture

This was a guest post for CORE education, which originally appeared as: Making the change we know in our hearts is essential…by building a coaching culture.

Today’s leaders are expected to work well with people. This expectation includes being able to help people to grasp the courage to act, develop new ideas, take risks, and “make the changes that we know in our hearts are essential and right in the world” (Robertson, 2015, p. 15). A strong mentoring or coaching relationship is one way of supporting people to do this. As a result, globally, a wide range of organisations — including schools, kura, and early childhood centres — are developing a coaching culture (Weekes, 2008).

These organisations hope to realise a wide range of benefits for educators, students, and the wider community including personal (and professional) growth (Hay, 1995); resilience in the face of change; support of innovation and ‘passion projects’; and the fostering of leadership and personal effectiveness. Coaching, when framed as an approach to communication where the empowerment of the people being coached is emphasised (Hoole, & Riddle, 2015), helps create positive learning environments. It also helps incubate a range of leadership approaches — something that research findings indicate have significant impacts on performance and wellbeing, as well as associated health benefits (Hoole, & Riddle, 2015).

What is a coaching culture?

At its root, a coaching culture is a model that structures and helps define the parameters of what effective interpersonal interactions look and feel like within a school, kura, or centre. Coaching would not be the only approach used in the organisation, but it would be used wherever appropriate. These structures and parameters are firmly underpinned by the values of the organisation, and can support the development of agreed ways of communicating, collaborating, and working together (Behavioral Coaching Institute, 2007).

However, sometimes, coaching may have a negative reputation within an organisation because, for instance, managers have previously used it as a performance management tool rather than as a genuine way to support professional learning and development. In these cases, a concerted effort will be needed to reframe coaching to help ensure that it is perceived positively, and part of this will be to support managers to develop their own coaching skills.

A well-established coaching culture will be one where coaching methodologies are ‘normalised’ within the organisation. For instance, it will be the preferred way of having conversations (Hoole, & Riddle, 2015). When this occurs, all people within the culture “fearlessly engage in candid, respectful coaching conversations, unrestricted by reporting relationships, about how they can improve their working relationships” (Crane, 2005, para. 3). These conversations will make use of coaching tools and the language of coaching to become part of the everyday way of working together. As a result, everyone values coaching as an integral part of personal and professional development — as a way of continually learning, improving practice, and positively contributing to the organisation’s goals.

The importance of providing a coaching programme to develop a coaching culture

An integral part of nurturing a coaching culture within a school, kura, or centre is ensuring that staff and students / ākonga are provided with formal opportunities to develop their own coaching skills. Otherwise, the tendency is for people to default to the neurologically energy-efficient approach of telling, which “requires less intellectual and emotional energy than engaging …[someone] in a thought process to advance their capability” (Hoole, & Riddle, 2015, Para 29).

A coaching programme will help staff and students / ākonga develop conceptual connections and explore implications for their organisation and the wider community. The long-term nature of the resulting changes can make a large-scale impact on everyone’s wellbeing, as well as how well the organisation functions.

Coaching managers will need to be coached themselves prior to taking on a coaching role. They will also need the ongoing support of their coach to help them continue to develop strong coaching skills, and to use integrity and patience to build the trust with their coachees. A coaching manager’s “ability to deeply listen is just as important as asking the questions that count” (Robertson, 2015, p. 12), especially where the goal is to ensure the coachee feels “sufficiently safe to move away from covering up any perceived areas of weakness” (Robertson, 2015, p. 12).

Coaching managers will need to be coached themselves prior to taking on a coaching role. They will also need the ongoing support of their coach to help them continue to develop strong coaching skills, and to use integrity and patience to build the trust with their coachees. A coaching manager’s “ability to deeply listen is just as important as asking the questions that count” (Robertson, 2015, p. 12), especially where the goal is to ensure the coachee feels “sufficiently safe to move away from covering up any perceived areas of weakness” (Robertson, 2015, p. 12).

It takes time to develop a coaching culture (up to a year or 18 months) because people need to be comfortable within the culture, and this provides sufficient time for everyone to develop the necessary coaching skills (The Open Door Coaching Group, 2012).

One consideration

By definition, a manager is not ideally placed to work as a coach or mentor for someone who is reporting directly to them. Robertson (2015) advises that vulnerability, power relations or conflicts of purpose “can adversely affect the relationship” (Robertson, 2015, p. 12).

What does the development of a coaching culture look like in practice?

Midtown School has a focus on across-school change, plus a desire to sustain the changes by implementing a coaching culture. After some robust discussions, the decision was made to go for a combination of face-to-face, whole school Professional Learning and Development, combined with virtual mentoring and coaching support for the leadership team who would then help to nurture a coaching culture throughout the school. Using the suite of products and services that CORE Education has available, the school decided to go for four face-to-face sessions (once a term), which were also supported by 18 months of uChoose virtual mentoring sessions for the leadership team.

Over the first six months with their virtual mentor the leadership team planned how they were going to introduce, support, and build sustainability into the coaching culture focus. They surveyed the staff, students and community, and gathered feedback data. The data provided some great insights into where people were most enthusiastic, plus, where the main support was going to be required. Alongside the planning, the leadership team with their mentor, worked with a range of coaching tools and approaches, trialled them with their teams, and then reflected together on how it went, and what they might change.

During the second half of the year working in the uChoose programme, after a whole-school session that focused on coaching, the leadership team rolled out some ‘quick dip, how to’ coaching sessions. Although it was a slow start, groups within the school started to increase their deliberate acts of coaching and coaching conversations, with some positive results.

In the new year, after 16 months of working to develop a coaching culture, it was clear that things were starting to consolidate, and it was noticed that:

- There was a school-wide identity with, and commitment to, the development of a coaching culture, with all staff and ākonga / students knowing most of the goals, as well as the contributions they could make in achieving them.

- There was increased enthusiasm and commitment to the overall school change initiative, with leaders and champions emerging from both the staff and the students / ākonga. They were jumping in to develop ‘passion projects’, initiatives with ‘an impact’, projects that were helping to enhance multicultural perspectives and practices, and as well as sustainable initiatives within the community.

- Several staff reported an increase in confidence in their interactions with each other, the students / ākonga, and the community.

- There appeared to be fewer humdinger’ arguments — although important, sometimes challenging conversations occurred more frequently.

- Positive feedback was offered more frequently, and was as objective as possible by removing the ‘personal’, while also ensuring that it was relevant.

- Staff and students who were new to the school were supported by a recently established initiative that helped them identify their strengths, find their place and to grow within the school

Conclusion

A coaching culture will not solve all an organisation’s challenges, nor will it guarantee that change will be successfully implemented and sustained. However, a school, kura, or centre with a strong coaching culture is likely to encourage a positive working environment, cross-community innovation, increased productivity — and lead to increased personal and professional growth and wellbeing. This in turn can help ensure that the organisation remains responsive and nimble in today’s world of fast-paced communication, diversity, global competition and change. Are you up for it?

Want to know more about uChoose?

Whanake haere ō mahi mā roto mai i ngā whatunga ngaio whai take

Evolving practice through responsive professional partnerships

Evolving practice through responsive professional partnerships

uChoose is mentored online professional learning, tailored to you and your learning journey.

Our experienced mentors work with you to identify and meet your professional needs, through supporting and challenging your thinking. Your mentor will also identify resources or activities that you will find useful to achieve your goals, or assist you in unpacking items of your own selection that you would like to work through.

Our experienced mentors work with you to identify and meet your professional needs, through supporting and challenging your thinking. Your mentor will also identify resources or activities that you will find useful to achieve your goals, or assist you in unpacking items of your own selection that you would like to work through.

References

Behavioral Coaching Institute. (2007). Establishing a coaching culture. Retrieved fromhttp://www.1to1coachingschool.com/Coaching_Culture_in_the_workplace.htm

Crane, T. (2005). Creating a COACHING CULTURE – today’s most potent organizational change process for creating a “high-performance” culture. Business coaching worldwide ezine, 1(1). Retrieved fromhttps://www.wabccoaches.com/bcw/2005_v1_i1/feature.html

Hay, J. (1995). Transformational Mentoring: Creating Developmental Alliances. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Publishing Co.

Hoole, E., & Riddle, D. (2015). The Intricacies of Creating a ‘Coaching Culture’. Retrieved from http://www.talentmgt.com/articles/7627-the-intricacies-of-creating-a-coaching-culture

Robertson, J. (2015). Deep learning conversations and how coaching relationships can enable them. Australian Education Leader 37(3). 10-15.

The Open Door Coaching Group. (2012). How do I build a coaching culture. Retrieved from http://www.opendoorcoaching.com.au/how-do-i-build-a-coaching-culture

Weekes, S. (2008, July). Catch on to coaching. The Edge. 28 – 32. Retrieved from http://qedcoaching.fastnet.co.uk/pdf/catch-on-to-coaching-ilm-edge-article.pdf

Images

- ‘Monarch butterfly emerging from chrysalis’ Found on flickrcc.net

- Seedling. CC ( BY NC ND) licensed Flickr image by Hazelowendmc

- Weave. CC ( BY NC ND) licensed Flickr image by Hazelowendmc

Monday, August 1, 2016

Are you a manager, a leader, or both?

What is leadership within professional environments - and how does it differ from management? There have been whole books written on the nuances, but in a nutshell: a manager plans, organises and coordinates a group a group or a set of entities to accomplish a goal, whereas a leader influences, inspires, motivates, and enables others to contribute to achieving organisational aims and success (Murray, n.d.). This definition does not preclude a manager being a leader, or a leader also being a manager. Rather they are overlapping, complementary roles.

What is leadership within professional environments - and how does it differ from management? There have been whole books written on the nuances, but in a nutshell: a manager plans, organises and coordinates a group a group or a set of entities to accomplish a goal, whereas a leader influences, inspires, motivates, and enables others to contribute to achieving organisational aims and success (Murray, n.d.). This definition does not preclude a manager being a leader, or a leader also being a manager. Rather they are overlapping, complementary roles.

If you are going to work on leadership or management skills, it is worth unpacking this a bit more, and identifying some of the key differences.

A manager... |

A leader... |

administers and plans detail

|

innovates and sets direction

|

directs groups

|

builds teams and talent

|

maintains and communicates

|

persuades and develops

|

focuses on systems and structures

|

focuses on people

|

controls and directs

|

Inspires, influences and facilitates

|

short-term view

|

long-term perspective

|

asks how and when

|

asks why

|

has objectives and are focussed

|

has vision and creates shared focus

|

accepts the status quo

|

challenges the status quo

|

react to change

|

create change

|

have people who work for them

|

have people who work with them

|

René Carayol (2011), suggests that we “manage a little less and lead a little more”, because the positive culture (‘the way we get things done around here’) within an organisation is much more powerful than strategy. Also, while organisations can have similar strategies, the thing that makes an organisation unique is its culture.

So, while management and leadership go hand-in-hand, supporting the growth of leaders within an organisation can help ensure that an organisation’s heritage is not its destiny - that opinions and processes change because the culture is supportive of that change.

References

Carayol, R. (2011). Authentic leadership [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g1ACR-odNR4&feature=related <Murray, A. (n.d.). What is the Difference Between Management and Leadership? Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from http://guides.wsj.com/management/developing-a-leadership-style/what-is-the-difference-between-management-and-leadership/.Image

Juggling balls. CC ( BY ) licensed Flickr image by William Warby: https://flic.kr/p/j9EWYVFriday, June 24, 2016

Is there a difference? Mentoring and coaching different genders

This is an extract from a blog that really caught my attention!

“I realize that I am more inclined to coach women. I have recently become aware that, although I have two sons and a great husband, all of whom I have close and cherished relationships with, I am not in a man’s life or a man’s body or brain. I cannot view the world from their perspective and experience.

Because I have no brothers, a struggling first marriage and am sometimes very surprised by a male perspective on things, when my husband and I were first together, I often “interviewed” my husband about a man’s perspective on things so I could learn. That being said, I notice that most women – including me, are more emotional and more easily connected to spirit or a spiritual perspective. I have a different experience of the world just because I have different cultural biases, a different functioning body, I use makeup, I wear dresses and skirts not just pants, the media sees me differently, etc. I think it’s safe to say there are some gender differences even if they are culturally stimulated.So I tend to have female clients with some notable exceptions like a single parent father with a child and a female ex- to deal with. I know that I am more drawn to talk about certain things with women – sex, feelings, even business perspectives. I am not saying one is better than the other for a woman. Just different. I often have had some great short-term coaching from my husband and occasionally some other male coaches but most likely I’d never hire a male coach for an on-going experience. I need a women’s coach.”

Source: Maia Berens, http://youuniversityonline.com/

I must admit to having quite a visceral reaction to the post I have quoted from above. As a woman I could never assume to know what a ‘man’s’ perspective is (if there were such a thing), just as I can’t assume I know any other human’s perspective of life and their place in the world. One of the joys of mentoring and coaching is that I am constantly surprised by my mentees’ and coachees’ viewpoints - but not more by one gender than the other.

I see my coachees and mentees as whole, culturally shaped, human beings who may or may not identify as male, female, transgender, androgynous, or bigender. People vary in their emotional and spiritual engagement during our sessions - with tears, for example. I also work mainly online, so I am unsure whether my my coachees and mentees are wearing makeup and I cannot see the clothes they are wearing. The subjects covered are varied and diverse, and do not appear to be gender specific. My role, I feel, is to respect each person - to listen to them, try my absolute best not to make assumptions, and to let them ‘take me’ where they need to go.

I have no personal preference for male or female coachees and mentees, nor for my own coaches and mentors. I have a preference for a coach or mentor who is non-directive, has a developmental approach, and asks really powerful questions - something I have experienced with males and females.

The research still isn’t available to say whether the human brain is ‘gendered’, and the most reliable evidence we have “suggests that both males and females share the same neural circuitry, but use it differently” (Stix, 2015, n.p.). Neuroscientists have found “few differences: more neurons or more neuronal spines here and there in one sex or the other, with great variations from one individual to the other but that’s about it” (Stix, 2015, n.p.).

So, I feel, while we are, for certain, shaped by our society and our culture - and how we perceive ourselves within a range of contexts impacts how we live our lives - when it comes to coaching and mentoring an attempt to make generalisations based on gender are not helpful. In fact, in some cases, they can reinforce damaging stereotypes.

Maybe I'm missing something? What are your thoughts?

Reference: Stix, G. (2015). Is the Brain Gendered? A Q&A with Harvard's Catherine Dulac. Retrieved fromhttp://blogs.scientificamerican.com/talking-back/is-the-brain-gendereda-q-a-with-harvard-s-catherine-dulac/

Image: Woman thinking. CC ( BY NC ) licensed Flickr image by patriziasoliani: https://flic.kr/p/9cdeng

Thursday, June 16, 2016

Developing connections and exploring implications through coaching

Most of today’s leaders are expected to deal effectively with people ́s motivation and be able to inspire them to their best performance. An essential part of this is fostering the courage to act, develop new ideas, take risks, and “make the changes that we know in our hearts are essential and right in the world” (Robertson, 2015, p. 15), and a strong coaching relationship is one way of supporting employees to do this. As such coaching skills need to be an integral part of any modern manager’s toolkit.

Most of today’s leaders are expected to deal effectively with people ́s motivation and be able to inspire them to their best performance. An essential part of this is fostering the courage to act, develop new ideas, take risks, and “make the changes that we know in our hearts are essential and right in the world” (Robertson, 2015, p. 15), and a strong coaching relationship is one way of supporting employees to do this. As such coaching skills need to be an integral part of any modern manager’s toolkit.

However, sometimes coaching in an organisation will also have a negative reputation because, for instance, managers have previously used it as a performance management tool, rather than as a genuine way to support employees’ professional learning and development. In these cases there will need to be a concerted effort to reframe coaching to help ensure it is perceived positively, and part of this is likely to be supporting managers to develop their own coaching skills.

One of the first considerations is that, by definition, a manager is not ideally placed to work as a coach for someone who is reporting directly to them. Robertson (2015) advises that vulnerability, power relations or conflicts of purpose “can adversely affect the relationship. But these tensions are not insurmountable if the relationship is sensitively negotiated and understood” (Robertson, 2015, p. 12).

A coaching manager will need to be a coachee themselves prior to taking on a coachee of their own. They will also need the ongoing support of their own coach to help them continue to develop strong coaching skills, and to use integrity and patience to build the trust with the coachees on their team. A coaching manager’s “ability to deeply listen is just as important as asking the questions that count” (Robertson, 2015, p. 12), especially where the goal is to ensure the coachee feels “sufficiently safe to move away from covering up any perceived areas of weakness” (Robertson, 2015, p. 12). Over time, as the coaching relationship matures, ultimately both the coaching manager and the coachee should become more aware of shifts in perspectives and thinking, “eventually introducing conflict to promote self-examination and further development of alternative perspectives” (Stokes, 2011, p. 8). Other factors Stokes (2011) identified as critical to the relationship were motivation, recognition and celebration of positive growth, and the provision of “a mirror… to extend the...[coachee’s] self-awareness” (Daloz, 1986, in Stokes, 2011, p. 8). These factors help a coaching manager and coachee watch for indications “that the relationship may be transformative and growth producing for both partners” (Stokes, 2011, p. 8).

Whilst the primary purpose of a coaching relationship is to help the coachee, nevertheless usually both the coaching manager and the coachee gain from the experience. For instance a coaching manager is likely to find that there is real satisfaction in helping another person to learn and grow in confidence and self-esteem, while they also practise and enhance skills, such as the ability to listen and question, to support and challenge, and to be non-directive and non-judgmental (Manukau Institute of Technology, 2009). Listening to the coachee can provide a fresh perspective and range of insights into an organisation’s culture and way of working, as well as the products and services they provide (Manukau Institute of Technology, 2009).

As indicated above, coaching managers play a fundamental part in building the future capability of employees and the organisation in which they both work, particularly by helping some of its talented professionals develop further than they might if they were not involved in a coaching relationship. As such, a coaching manager can support their coachee to:

- learn by reflecting on their experiences

- develop their confidence and professional skills

- work on tricky or challenging relationships

- identify areas that they would like to develop in their practice, and to set SMART goals

- increase their ability to take responsibility for own decisions

- identify professional and/or interpersonal skills they would like to develop

- plan - a project, their next steps, and/or their career

- develop their own leadership skills, and be comfortable working within an organisation where delegation is the norm

- enhance business efficiency / processes

(Adapted from Manukau Institute of Technology, 2009)

Some of the practical ways in which coaching can be applied in modern management are by:

- providing coaching as a part of every employee’s work, especially for Generation Z, to help meet a need for one-to-one support and development. Coaching sessions would be scheduled in advance, regular, of a high priority, and illustrative of the importance the coaching manager gives to them.

- supporting coaching managers to work consistently with coachees on their specific skills (and confidence), in part through the development of professional learning plans. The plans would be discussed and negotiated with all members of their team, and there would be sufficient structure to help ensure that milestones were identified and measurable, and scheduled in a way that ensures regular feedback. Feedback might be via multimedia, as well as during coaching sessions. A coaching manager’s approach would need to be flexible so that the tone and approach match each team member’s needs and expectations.

- using coaching to make the most of the enthusiasm and commitment of all employees (in particular Generation Z). A coaching manager would available to help support emerging leaders and champions, who are seen as having the potential to go far in an organisation. They could be encouraged to take on leadership roles. Initially, these might be around, for instance, ‘passion projects’, initiatives with ‘an impact’, projects that would help enhance multicultural perspectives and practices within the company, or sustainable working within the company.

- helping an employee who is technically very capable but struggling to develop effective ways of integrating this into their professional practice, especially while interacting with customers. Regular feedback and monitoring of progress toward SMART goals would be part of the coaching manager’s role. The coaching manager would also make sure that positive feedback was given frequently, and was as objective as possible by removing the ‘personal’, while also ensuring that it was relevant.

- ensuring that an employee feels supported as they work on tricky or challenging professional relationships, within the business as well as with clients. The coaching manager would need to listen as much as question to help the coachee feel heard in regards to their experiences, while also supporting the coachee to develop their own solutions and strategies.

- building a culture where taking risks, and learning from mistakes is welcomed and a part of the company culture as well as part of the healthy coaching relationships. When mistakes were made, the managing coach would ensure that the coachee reflects critically, ‘owns’ the learnings, and identifies next steps. This would help ensure that the managing coach’s role remains (and is perceived as by their team) formative in focus.

- assisting someone who has recently joined the organisation, or taken on a leadership role, to find their feet. A coaching manager’s role would be to help the coachee identify the skills and knowledge that would help them find their place and grow in the organisation. In part this would be through the coaching manager’s own extensive knowledge and experience of the organisation’s culture, processes, products and services.

- encouraging team members who have a tendency to under-perform to develop their awareness of this, and (where the employee is coachable - i.e. willing to learn and change in a coaching relationship) motivate them to change their behaviour. A coaching manager’s role would be to support the coachee to reflect on their practice, how they are interacting in the team and with customers, and ensuring that the coachee outlines their own goals, actions, and ways of evaluating success. The coaching manager would then need to follow up frequently, and to identify if the coaching was not working.

If people “learn best when they see a practical application of the new knowledge / skill in their job and / or daily life” (Southern Institute of Technology, n.d.), coaching can enhance this tendency by helping an employee develop conceptual connections and explore implications for their team and the wider organisation. The long-term nature of the resulting changes can make a large-scale impact on how well an organisation functions, how content the workforce feels, and in turn, how much their customers value it. As such, coaching managers play an essential part in helping to ensure an organisation’s efficiency and profitability.

References

Aas, M, & Vavik, M. (2015). Group coaching: a new way of constructing leadership identity?, School Leadership & Management: Formerly School Organisation. 35(3). 251-265.

American Management Association. (2008). Coaching: A Global Study of Successful Practices - Current Trends and Future Possibilities 2008-2018. Retrieved from https://www.opm.gov/WIKI/uploads/docs/Wiki/OPM/training/i4cp-coaching.pdf

Brent, M. (n.d.). Why Don’t More Managers Coach? Retrieved from http://www.ashridge.org.uk

Cheslow, D. (2013). The Coachability Index. Retrieved from http://www.debcheslow.com/the-coachability-index/

Gitsham, M., & Wackrill, J. (2012). Leadership in a rapidly changing world: How business leaders are reframing success. Retrieved from http://www.ashridge.org.uk/Website/Content.nsf/FileLibrary/444E6C7531EC5EFD802579CE0048E830/$ file/Leadership%20Mar%202012-print.pdf

Harkins, P. (2005). Getting the organisation to click. In H. Morgan, P. Harkins, & M. Goldsmith (Eds.), Leadership coaching: 50 top executive coaches reveal their secrets (2nd ed., pp. 154-158). Hoboken, NJ: John Wileys & Sons.

Hay, J. (1995). Transformational Mentoring: Creating Developmental Alliances. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Publishing Co.

Krishna, R. R. (2015). The coachability index. Retrieved from http://coachfederation.org/blog/index.php/4301/

Manukau Institute of Technology. (2009). Mentoring Guidelines and Mentor Training Resource. Retrieved from https://akoaotearoa.ac.nz/ako-hub/ako-aotearoa-northern-hub/resources/pages/mentoring-guidelines

McLagan, P. A. (2000, February). Portfolio Thinking: Performance Management in the New World of Work. Training and Development. 44-52. Retrieved from http://www.workinfo.com/free/downloads/229.htm

Owen, Hazel; Dunham, Nicola. (2015). Reflections on the Use of Iterative, Agile and Collaborative Approaches for Blended Flipped Learning Development. Educ. Sci. 5(2). 85-103.

Owen, H. (2015 a). Making the most of mobility: virtual mentoring and education practitioner professional development. Research in Learning Technology 2015 (ALTJ), 23, 25566.

Owen (2015 b). Professional learning, any time, any place with virtual mentoring. EDULEARN15 Proceedings, pp. 386-393.

Robertson, J. (2015). Deep learning conversations and how coaching relationships can enable them. Australian Education Leader 37(3). 10-15.

Southern Institute of Technology. (n.d.) Whom can I coach? (Module D) [Lecture notes]. Retrieved from CBC101 (NET).

Weekes, S. (2008, July). Catch on to coaching. The Edge. 28 - 32. Retrieved from http://qedcoaching.fastnet.co.uk/pdf/catch-on-to-coaching-ilm-edge-article.pdf

Whitmore, J. (2009). Will coaching rise to the challenge? The OCM Coach and Mentor Journal, 2-3.

Image

Jumping. CC ( BY NC ND ) licensed Flickr image by Bernat Casero: https://flic.kr/p/3ewuQn

Tuesday, May 10, 2016

Wheels within wheels - ways to help you make decisions

Everyone has times when they have two (or more) alternatives to choose from and are not sure how to make a choice that they feel they won’t regret later on. They may have already made a pros and cons list for each and tried to make a comparison, but still feel it isn’t clear which choice is likely to be best for them.

Two coaching wheels

Coaching can be a great way to work through this situation. When a person asks me to work through it with them, one tool I use is the coaching wheel as it helps chunk the options and prioritise them. However, instead of using one version of the coaching wheel, we’ll use two, with each wheel representing an option.

I work with the coachee to identify the key factors for them that would span both options, and these would be listed, then written into both wheels. The next step is to, for both options (i.e. both of the wheels), revisit all of the factors and mark them, on a scale of 1 to 10, how well they are represented in each option (Southern Institute of Technology (a), n.d.). As a final step the factors are evaluated and a colour used to represent any that the coachee identifies as ‘non-negotiable’. Those that the coachee doesn’t see as non-negotiable can then be framed at a level the coachee wouldn’t negotiate below.

Tui: The two job offer dilemma

Usually, it becomes really clear, based on the coachee’s values and beliefs, which of the options makes the most sense for them. Take for example, a coachee, Tui, who has been making really strong progress toward her goals, and has applied for and been offered two jobs. Both roles seem like dream jobs and appear to offer great opportunities for career progression. Tui is anxious to make the ‘best’ decision. Which to choose?

The first step I take to support Tui is to ask her to visualise what her ideal job and role look and feel like. After a moment or two I then ask her to state the most important factors for her. Tui pauses to think, and then identifies: professional development, collaborative workplace, autonomy, opportunities for progression, opportunities to assume management responsibilities, close to home or near public transport, has a cafeteria that has healthy eating options, and has a gym on the premises or nearby. I am taking notes while the Tui is talking so that she can focus on her thoughts rather than on writing them down. The notes are useful in the next step where I ask her to double check the list of criteria. She confirms that it looks complete and these are the criteria she wants to use.

Using two blank coaching wheels I invite Tui to add in the criteria, and to place each section on the 1 to 10 scale. After she has completed that step, I then ask Tui how important the criteria are to her, and if there are any on which she might compromise. Having chosen ‘opportunities to assume management responsibilities, opportunities for progression, and a gym on the premises or nearby’ as her non-negotiables, she then colours these sections green. ‘Professional development, collaborative workplace, and autonomy’ she identifies are open for some negotiation and she colours these orange. The remaining ones she colours blue.

It is immediately clear to Tui and I, just by looking at the prevalence of green on one of the wheels, that this job is the job that will be the better fit according to Tui’s criteria. Tui is both relieved and delighted. She reveals that she had a gut feeling about the job that came out on top, and is pleased that she can make an informed decision that reflects her priorities. The job, she feels will stretch her, but she has the peace of mind that it will be in a way that will develop her strengths and move her in the direction she wants to go - and she is likely to get a bit fitter!

Other uses

There is the option where there are more than two choices more than two wheels can be used, but this can become a bit cumbersome. Also, the approach with two or three wheels can be used when coaching a group. For instance, where a team have to decide between two or more ways forward, and feel as though they are talking in circles. The wheels can be a great way to focus discussions about team values and beliefs. They can also help to ‘depersonalise’ some of the priorities through the use of the visual representation, which clearly illustrates, in one place, the overall team’s criteria.

The main benefit

While it isn’t a watertight approach, using two coaching wheels as a tool to make comparisons does help ensure that the coachee is empowered to make a decision based on their strengths, values, and beliefs. This means that whichever one they choose is likely to be the ‘best’...for them.

References

- Personal Coaching Information. (n.d.). Scaling Techniques In Coaching For Assessing Progress. Retrieved from: http://www.personal-coaching-information.com/scaling-techniques-in-coaching.html

- Wallis, G. (2013). One a scale of 1 to 10. Retrieved from http://www.theexecutivecoachingblog.com/2013/02/27/on-a-scale-of-1-to-10/

Image

Russian Matryoshka. CC ( BY ND NC ) licensed Flickr image by Dennis Jarvis: https://flic.kr/p/7z5fiG

Tuesday, May 3, 2016

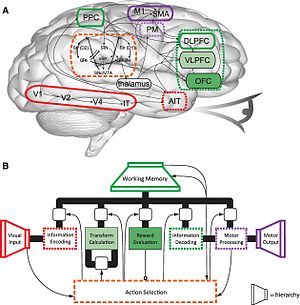

A brief overview of cognitive computing

Information is unstructured, especially when it is en masse (think, for instance, the Internet). The amount of available content is doubling every 5 years, and we just don't have the time or the cognitive capacity to keep up with everything.

Information is unstructured, especially when it is en masse (think, for instance, the Internet). The amount of available content is doubling every 5 years, and we just don't have the time or the cognitive capacity to keep up with everything.People have amazing ideas, but the computational abilities are often not ready. "At the core we are trying to leverage knowledge the way humans record and communicate in natural human language in a a particular text" (video below), to the point where there is a natural interaction between humans and computers". Ideally, cognitive computing systems expand the boundaries of human cognition and get smarter with use, providing complex information processing systems, able to acquire information, collate and act on it, and transmit it as knowledge.

For example, healthcare. In healthcare cognitive computing can become a "support tool to expand the physicians cognitive boundaries by giving them deeper access to much larger volumes of [selected, filtered, organised] information" (video below). In other words, we are leveraging the computer's ability to keep up with huge volumes of data. Using semantic analysis to recognise patterns the computer is able to understand the knowledge contained within the data, so that it can be applied to the problem that the physician is trying to solve, and give different alternatives, while also providing evidence that supports those alternatives (evidence exploration). The key here is that we are "adapting the computer technology to work better with the way humans want to work so it's a more natural relationship between the human and computer" (video below).

A useful visual introduction cognitive computing, the video (2 mins 6 secs) below, Eric Brown (IBM Research) provides a brief overview referring in particular to Watson. For a much deeper overview, have a read of What is cognitive computing ? IBM Watson as an example.

Image: Simplified diagram of Spaun, a 2.5-million-neuron computational model of the brain. Public domain licensed Wikimedia Commons image by Chris Eliasmith: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Architecture_of_Spaun.jpeg

Tuesday, April 26, 2016

Time for dreaming, criticising, and being realistic....

I sometimes work with coachees who will come up with a strategy, and then immediately add the tag “that won’t work because…”. This focus tends to result in some great ideas and strategies never getting off the ground as a result.

I sometimes work with coachees who will come up with a strategy, and then immediately add the tag “that won’t work because…”. This focus tends to result in some great ideas and strategies never getting off the ground as a result.

The Disney Strategy was developed by the Neuro Linguistic Programme (NLP) practitioner, Robert Dilts. Dilts based the strategy on the approach Walt Disney used with his creative teams to support them to develop ideas. The underpinning concept is that, even if a person has a way of thinking that they find most comfortable, any person can consider something from three different perspectives and switch between them. The approach can be used with individuals, or with small and large groups.

The reason the Disney Strategy works so well in situations where the person is their own worst critic of their ideas is because of the three separate modes: Dreamer, realist, and critic. The strategy, even when coachees are initially sceptical, is effective in part because it also acknowledges a coachee’s perceived barriers - but not until they have explored their initial ideas.

The Dreamer mode is where I encourage all the coachee’s new ideas - the focus here is purely on (positive) creative suggestions and on invention. The sky’s the limit! Barriers and issues have no place here because they are acknowledged in the next two modes.

In the Realist mode I encourage my coachee to consider how to make their ideas work in practice. This is the mode where ideas become detailed plans (with milestones and timelines) that are likely to work in the coachee’s context because it integrates complexities.

The final mode, the Critic gives space for the coachee to look for flaws in their ideas and to identify what might go wrong. This mode helps ensure that the coachee ‘audits’ their idea, registers risks, and considers mitigations; it is a way of keeping the best of an idea - maybe using it as a springboard for a second idea - at which point the coachee and I would work through all 3 modes again. Alternatively, possible big picture fixes could be taken back the the dreamer mode and other two modes again if an idea still holds merit but has some apparent issues.

I carefully facilitate each mode, clearly defining the associated ‘rules’ and describing the modes. Shifts from mode to mode can also be signalled by different coloured items of clothing if the approach feels comfortable.

In brief the Disney Strategy provides time and opportunities for an idea mature and develop because:

- My coachee can generate a range of ideas quickly, and cannot immediately jump on what they see as flaws, concerns or risks.

- Idea / brainstorming spaces can be shared in advance of a coaching session to start the coachee’s creative energies flowing.

- Using communication links between the dreamer and realist, and then the realist to critic, avoids the critic directly making comment about an idea in the early stages, thereby keeping the energy level high and positive during the dreamer mode.

- The approach can break habits of constantly scanning for, and criticising, flaws in a suggestion, which can clear the ‘log-jam’ and allow ideas to flow more freely (i.e. less “that won’t work here because…”.

- By working through one mode at a time, the dialogue remains focussed and is not undermined by the possible distractions caused by the other modes.

- Ideas that have gone through the Disney Strategy are likely to be way more robust.

Image

Message stones. CC ( BY ND ) licensed Flickr image by: Roselyn Rosesline - https://flic.kr/p/eTzoib

Tuesday, April 12, 2016

Getting your goals right

Coaching has a wide range of definitions and approaches. One of the most prevalent understandings is that coaching comprises “a collaborative relationship formed between a coach and the coachee for the purpose of attaining professional or personal development outcomes which are valued by the coachee” (Spence & Grant, 2007, p. 185). Couched within this understanding is the importance of goal-focused activity with a clearly defined outcome. A person embarks on a coaching relationship because they are working through a challenge, or a goal that they want to attain, and they are looking for support to develop effective strategies and solutions (Grant, 2013). As such, a big part of development is setting effective goals that will enable a person to plan and identify clear directions to achieve their desired change.

Coaching has a wide range of definitions and approaches. One of the most prevalent understandings is that coaching comprises “a collaborative relationship formed between a coach and the coachee for the purpose of attaining professional or personal development outcomes which are valued by the coachee” (Spence & Grant, 2007, p. 185). Couched within this understanding is the importance of goal-focused activity with a clearly defined outcome. A person embarks on a coaching relationship because they are working through a challenge, or a goal that they want to attain, and they are looking for support to develop effective strategies and solutions (Grant, 2013). As such, a big part of development is setting effective goals that will enable a person to plan and identify clear directions to achieve their desired change.

Beyond the practical aspects of goal-setting, research indicates that setting and evaluating your own goals play a large part in sustained motivation and ongoing action, even in the face of emerging issues (Bandura, 1998). The process of associating attainment of stated (valued) goals with self-satisfaction has a direct influence on “how much effort [a coachee]... expend[s]; how long they persevere in the face of difficulties; and their resilience to failures … [and these contribute] to performance accomplishments” (Bandura, 1998, p. 75).

There are several characteristics to effective goals … and some common mistakes. I’m now going to briefly discuss a few of them.

Challenging but attainable

Goals need to stretch you, but still be attainable .. within your stated timeframe. So, if you have never run a step in your life and are not in the best of shape, it is unlikely, for example, that you will attain a goal of winning a marathon in a month’s time. However, if you decide you would like to run a marathon in say, 4 hours, in a year’s time, and put together a training plan with milestone goals along the way, then you are likely to achieve it. So, a long-term goal, with incremental steps (and celebrations) along the way, and with enough challenge to keep you interested, is the way to go.

Specific and within a timeframe

A mistake that is often made is to identify a goal that says we will try harder, do more of something, or improve a skill. However - how will you know you are making progress, or have achieved what you have set out to without some ‘measure’ that will enable you to evaluate how you are doing. You goals should be as tangible as possible, and specify how many, of what, and by when. Using the example above about the marathon, if, as a sub goal you decide to run the Auckland 10km race in April in under 1 and a half hours, it would be easy to know if you have or have not achieved the goal. It’s not always easy to set such specific goals, but the more specific you can be the greater your sense of progress will be.

Positive

Sometimes it’s tempting to identify what we don’t want - things (emotions, behaviours, contexts) we’d like to avoid - rather than looking at what we do want. It is, though, way easier to actively set out to do or achieve something than it is to try to avoid doing it. Again, taking the example of the marathon, compare ‘I will stop eating biscuits until after I have run the marathon’, with ‘Up to when I run the marathon I will eat at least one salad a day, except for Monday which is my day off when I will eat 1 biscuit’.

Other things to include in effective goals

As well as the three key areas discussed above, it is good to also keep in mind the following characteristics of effective goal setting so that you include:

- clear direction to attain your desired change,

- clarity of priorities (which will inform your ongoing decision making),

- identification of resources available to you (including people),

- clearly stated tasks and activities that align directly with specific aspects of your goal(s), and

- specific links to your performance and personal development

(Southern Institute of Technology, n.d., n.p.)

Even if you set effective goals, sometimes you’ll feel as though you aren’t making progress or that other things are derailing your efforts. At times like these it is good to talk with your coach to work through responses that will help you stick with your long-term goals, while maintaining your motivation - and sanity!

Terry Pratchett in his novel The Wee Free Men sums up the importance of goals as opposed to dreams as follows: “If you trust in yourself. . .and believe in your dreams. . .and follow your star. . . you'll still get beaten by people who spent their time working hard and learning things ...” (Pratchett, 2004, p. 21). Dreams can be incredibly motivating. However, you need to sit down and work out how to turn them into them reality, and setting effective goals is part of that process.

Image

Back in time. CC ( BY ND ) licensed Flickr image by Hartwig HKD: https://flic.kr/p/6zXq7Y

References

- Bandura, A. (1994). Self-efficacy. In V. S. Ramachaudran (Ed.), Encyclopedia of human behavior (Vol. 4, pp. 71-81). New York: Academic Press. (Reprinted in H. Friedman [Ed.], Encyclopedia of mental health. San Diego: Academic Press, 1998).

- Burdett, J. (2005). The listening paradox. Organizational Performance Review, 7-9.

- Castleberry, S., & Shepherd, C. D. (1993). Effective Interpersonal Listening and Personal Selling. Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management, XIII(1), 35-49.

- Grant, A. (2013). The Efficacy of Mentoring - the Benefits for Mentees, Mentors, and Organizations. In Jonathan Passmore, David B. Peterson, and Teresa Freire (Eds). The Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of the Psychology of Coaching and Mentoring Series: Wiley-Blackwell Handbooks in Organizational Psychology. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 16 - 34.

- International Coaching Federation. (n.d.). ICF Core Competencies. Retrieved from http://www.coachfederation.org/files/FileDownloads/CoreCompetencies.pdf.

- Pickering, M. (1986, Fall). Communication. Explorations, A Journal of Research of the University of Maine, 3(1). pp. 16-19.

- Rogers, C R., & Farson, R.E. (1987). Active listening. In Communication in Business Today. Eds. R. G. Newman, M. A. Danziger, & M. Cohen. Washington C.C.: Heath and Company

- Rothwell, J. D. (2010). In the company of others: An introduction to communication. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Salem, R. (2003). Empathic Listening. In Beyond Intractability. Eds. Guy Burgess and Heidi Burgess. Conflict Information Consortium, University of Colorado, Boulder. Retrieved http://www.beyondintractability.org/essay/empathic-listening

- Southern Institute of Technology. (n.d.) Transformational Coaching and its outcomes (Module A) [Lecture notes]. Retrieved from CBC105 (NET).

- Spence, G.B., & Grant, A. (2007) Professional and peer life coaching and the enhancement of goal striving and well-being: An exploratory study. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 2, 185–94.

- Whitworth, L, Kimsey-House, K, Kimsey-House, H, & Sandahl, P. (2007). Co-active coaching: New skills for coaching people toward success in work and life. Palo Alto,California: Davies-Black Publishing.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)